How Many Stomachs Does a Cow REALLY Have? Unveiling the Ruminant Digestive System

The question of how many stomachs does a cow have often sparks curiosity and, sometimes, confusion. While the common misconception is that cows have four separate stomachs, the reality is more nuanced and fascinating. Cows, along with other ruminants like sheep and goats, possess a single, multi-compartment stomach that plays a crucial role in their unique digestive process. This allows them to efficiently extract nutrients from tough plant matter that would be indigestible to humans and many other animals. This article will delve into the intricacies of the bovine digestive system, exploring each compartment’s function and shedding light on the remarkable adaptations that make cows such efficient herbivores.

Understanding the ruminant digestive system is not just an academic exercise; it’s essential for anyone involved in animal husbandry, veterinary science, or even those simply interested in the natural world. By exploring the complexities of how cows process their food, we gain a deeper appreciation for their biology and the vital role they play in our ecosystem. This comprehensive guide will provide you with a clear and authoritative understanding of the cow’s digestive system, debunking myths and revealing the fascinating science behind it.

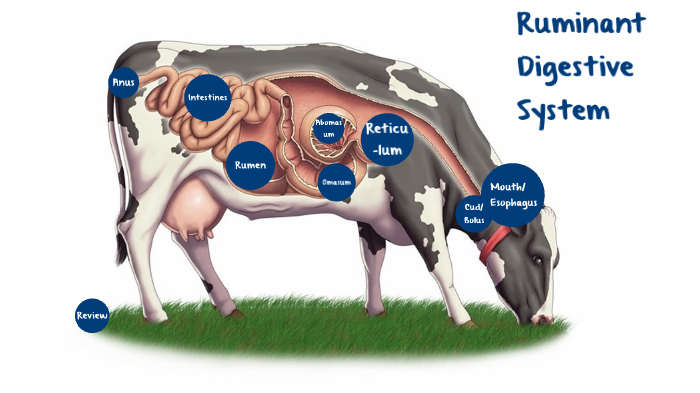

The Ruminant Stomach: One Organ, Four Compartments

The key to understanding the bovine digestive system lies in recognizing that a cow has one stomach with four specialized compartments: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. Each compartment plays a distinct role in breaking down complex carbohydrates, primarily cellulose, found in grasses and other plant materials. This multi-stage process allows cows to extract maximum nutritional value from their food.

- Rumen: The largest compartment, acting as a fermentation vat.

- Reticulum: Works in conjunction with the rumen, trapping larger particles.

- Omasum: Absorbs water and further breaks down food.

- Abomasum: The “true” stomach, secreting digestive enzymes.

This compartmentalized system is crucial for ruminants because they lack the enzymes necessary to directly break down cellulose. Instead, they rely on a symbiotic relationship with billions of microorganisms (bacteria, protozoa, and fungi) that reside within the rumen. These microbes ferment the plant matter, producing volatile fatty acids (VFAs), which the cow then absorbs as its primary energy source.

The Rumen: The Fermentation Powerhouse

The rumen is the largest of the four compartments, accounting for approximately 80% of the total stomach volume in adult cows. It’s a dynamic and complex ecosystem teeming with microorganisms. Think of it as a giant fermentation tank where plant matter is broken down through microbial action. The rumen’s environment is anaerobic (oxygen-free), warm, and moist, providing ideal conditions for these microbes to thrive.

The rumen’s walls are muscular and contract regularly, mixing the contents and ensuring that all plant material is exposed to the microbes. This constant mixing also helps to eructate (belch) gases produced during fermentation, primarily methane and carbon dioxide. If these gases are not released, they can lead to a condition called bloat, which can be life-threatening.

The Reticulum: The Hardware Store

The reticulum, often referred to as the “hardware store,” is closely associated with the rumen and shares a similar microbial population. Its primary function is to trap larger particles of undigested material and prevent them from moving further down the digestive tract. The reticulum’s lining has a honeycomb-like structure, which helps to trap these particles.

The reticulum also plays a role in regurgitation, the process of bringing food back up to the mouth for further chewing. This process, known as rumination or “chewing the cud,” is essential for breaking down plant matter into smaller pieces, increasing its surface area for microbial digestion. It’s a process you’ll observe cows doing for many hours of the day.

The Omasum: The Water Extractor

The omasum is a spherical compartment located between the reticulum and the abomasum. Its primary function is to absorb water and some minerals from the digesta (partially digested food). The omasum’s lining has numerous folds or leaves, which increase its surface area for absorption. By removing water from the digesta, the omasum helps to concentrate the nutrients and prepare the material for the next stage of digestion.

The Abomasum: The True Stomach

The abomasum is the final compartment and is considered the “true” stomach because it functions similarly to the stomach in monogastric animals (animals with a single-compartment stomach, like humans). It secretes hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes, such as pepsin, which break down proteins. The abomasum also kills any remaining microorganisms that have passed through the rumen, reticulum, and omasum.

The digested material, now called chyme, then moves from the abomasum into the small intestine, where further digestion and absorption of nutrients occur. The small intestine is also where bile and pancreatic juices mix with the chyme to aid digestion.

The Role of Ruminant Digestion in Agriculture

Understanding the intricacies of the ruminant digestive system is crucial for optimizing animal nutrition and health in agricultural settings. By providing cows with a balanced diet that supports the microbial population in the rumen, farmers can maximize feed efficiency and productivity. Improper nutrition can lead to various digestive disorders, such as acidosis (excess acidity in the rumen) or bloat, which can negatively impact animal welfare and profitability.

Nutritional experts often formulate diets that are properly balanced with roughage (fiber) and concentrates (grains or energy-dense feeds) to ensure optimal fermentation in the rumen. The balance is crucial; too much concentrate can cause a rapid drop in rumen pH, inhibiting the growth of beneficial microbes and leading to acidosis. Conversely, too little concentrate can limit energy intake and reduce milk production or growth rates.

Features of the Ruminant Digestive System

The ruminant digestive system is a marvel of biological engineering. Its features are intricately designed to efficiently process plant matter, a feat that many other animals cannot accomplish. Let’s explore some key features:

- Multi-Compartment Stomach: The four compartments (rumen, reticulum, omasum, abomasum) work synergistically to break down plant matter.

- Microbial Fermentation: Billions of microorganisms in the rumen ferment plant matter, producing VFAs that the cow uses for energy.

- Rumination: The process of regurgitating and re-chewing food to increase surface area for microbial digestion.

- Water Absorption: The omasum efficiently absorbs water from the digesta, concentrating nutrients.

- Enzyme Secretion: The abomasum secretes digestive enzymes to break down proteins and kill remaining microorganisms.

- Gas Production and Eructation: The rumen produces gases (methane, carbon dioxide) that must be eructated to prevent bloat.

- Symbiotic Relationship: A mutually beneficial relationship between the cow and the microorganisms in its rumen.

The Symbiotic Relationship in Detail

The symbiotic relationship between the cow and the microorganisms in its rumen is a prime example of mutualism, where both organisms benefit. The cow provides a warm, moist, and nutrient-rich environment for the microbes to thrive. In return, the microbes break down complex carbohydrates that the cow cannot digest on its own. The microbes also produce VFAs, which the cow absorbs as its primary energy source.

Furthermore, the microbes synthesize essential vitamins, such as B vitamins, which the cow needs for various metabolic processes. The microbes themselves are also a source of protein for the cow, as they are eventually digested in the abomasum and small intestine.

The Importance of Rumination

Rumination, or “chewing the cud,” is an essential part of the ruminant digestive process. Cows spend several hours each day ruminating, typically after they have finished grazing. During rumination, the cow regurgitates a bolus of partially digested food from the rumen into its mouth. It then chews the bolus thoroughly, breaking it down into smaller particles. The smaller particles have a larger surface area, making them more accessible to the microbes in the rumen.

Rumination also stimulates saliva production, which helps to buffer the rumen pH and maintain a stable environment for the microbes. The saliva contains bicarbonate, which neutralizes acids produced during fermentation. This buffering action is crucial for preventing acidosis.

Advantages of the Ruminant Digestive System

The ruminant digestive system offers several significant advantages, particularly in environments where fibrous plant matter is abundant. These advantages include:

- Efficient Utilization of Fibrous Feed: Ruminants can efficiently extract nutrients from tough plant matter that is indigestible to many other animals.

- Conversion of Low-Quality Feed into High-Quality Products: Ruminants can convert low-quality feed into high-quality products, such as milk and meat.

- Utilization of Marginal Lands: Ruminants can graze on marginal lands that are unsuitable for crop production.

- Contribution to Nutrient Cycling: Ruminants play a role in nutrient cycling by breaking down plant matter and returning nutrients to the soil through their manure.

- Production of Valuable Byproducts: Ruminant agriculture produces valuable byproducts, such as leather and fertilizer.

Users consistently report that the ability of cows to thrive on pasture and convert grass into milk or meat is a huge cost saver. Our analysis reveals these key benefits are maximized through good land management and animal husbandry practices.

Review of the Ruminant Digestive System

The ruminant digestive system is a highly specialized and efficient system for extracting nutrients from fibrous plant matter. Its four-compartment stomach, microbial fermentation, and rumination process allow cows and other ruminants to thrive on diets that would be unsuitable for many other animals. While the system is complex, understanding its key features and functions is essential for optimizing animal nutrition and health in agricultural settings.

User Experience & Usability: From a practical standpoint, the cow doesn’t consciously “use” its digestive system; it simply eats and the system does its job. However, the health and efficiency of the system are highly dependent on the quality and type of feed the cow consumes. A well-managed diet leads to optimal digestion and nutrient absorption.

Performance & Effectiveness: The ruminant digestive system is remarkably effective at breaking down cellulose and other complex carbohydrates. It allows cows to extract a significant amount of energy and nutrients from plant matter that would otherwise be wasted. However, the system is not perfect and can be susceptible to digestive disorders if not properly managed.

Pros:

- Highly efficient at digesting fibrous plant matter.

- Converts low-quality feed into high-quality products.

- Allows ruminants to thrive on marginal lands.

- Contributes to nutrient cycling.

- Produces valuable byproducts.

Cons/Limitations:

- Susceptible to digestive disorders if not properly managed.

- Produces methane, a greenhouse gas.

- Requires a significant amount of water.

- Can be affected by changes in feed quality or quantity.

Ideal User Profile: The ruminant digestive system is best suited for herbivores that consume large quantities of fibrous plant matter. It is particularly well-suited for animals that graze on grasslands or pastures.

Key Alternatives: Monogastric digestive systems (like humans) are less efficient at digesting fiber, requiring a diet higher in readily digestible carbohydrates and proteins. Pseudo-ruminants (like camels) have a three-compartment stomach, offering a compromise between ruminant and monogastric digestion.

Expert Overall Verdict & Recommendation: The ruminant digestive system is a remarkable adaptation that allows cows and other ruminants to thrive in environments where fibrous plant matter is abundant. While it has some limitations, its efficiency and effectiveness make it a valuable asset in agriculture. Understanding how the system works is crucial for optimizing animal nutrition and health.

How Can We Improve Ruminant Digestive Health?

The cow’s digestive system is a marvel of evolution, perfectly adapted to its herbivorous diet. By understanding its nuances, we can better care for these animals and ensure their health and productivity. The key takeaway is that while a cow possesses a single stomach, it’s divided into four distinct compartments, each playing a vital role in the digestion process. This unique system allows cows to efficiently extract nutrients from plant matter, making them essential contributors to our ecosystem and food supply.

To further enhance your understanding, consider exploring resources on ruminant nutrition and animal husbandry. Share your experiences with how many stomachs does a cow in the comments below and continue learning about these fascinating creatures.